For a recap of an introduction to Aristotle's ideas, go to this link. (http://mrmacavastel.blogspot.com/2017/03/living-aristotelian-life-in-postmodern.html)

But let's look into what Aristotle wanted to teach us.

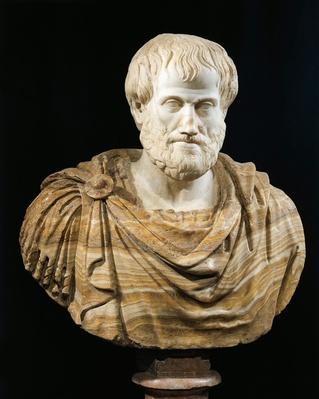

(https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/98953036-famous-mathematicians/marble-and-alabaster-bust-of-aristotle-famous-mathematicians/)

1) Find the Golden Mean

When Aristotle talks about finding the Golden Mean, he wants to find a scientific/logical balance of two extremes. But what's interesting is that he make an effort to find it in a very rational way. He explains, through reason, how finding the golden mean is a virtuous task. So since he explains how by using two specific virtues, we'll talk about them the most because he goes greatly into details with them: Courage and Generosity.

Courage is the virtue of bravely going into scenarios even when feeling fear. But when Aristotle looks at courage, he also looks at the extremes of Courage. In his eyes, there is an excess of a virtue and regress. For example, Courage is in-between Recklessness (The excess of Courage) and Cowardice (Regress).

Recklessness, in Aristotle's eyes, is blind courage without examining anything at all with the situation in mind. So when one needs to feel fear, there is none and there is no caution for even personal safety and reckless behaviors lead closely to death. Cowardice is the lack of any courage whatsoever. Refusing to stand up for one's self (or/and others) and living in fear is a true regress of Courage. Seeing these two extremes made Aristotle focus on finding the golden mean of the virtues.

Generosity is freely giving without it hurting oneself and in the spirit of helping those who deserve it. Aristotle focuses on the importance of righteousness when it comes to generosity because there is an amount that will be too much, we might give money when we shouldn't (I know someone terribly like this), and we might give it to the wrong people.

But let's focus on how he gets this by noticing the excess and regress of Generosity (called Liberality in many translations but we'll use Generosity due to many knowing the word more familiarly). The Regress, in this case, is Stinginess (a greediness focused on hoarding all goods and money, i.e. Ebineezer Scrooge the Miser). And for the Excess, ... well, Aristotle is unsure about the right word in this case. He refers to this as Wastefulness (as well as some Aristotle academics) but some use the word Profligacy. (I'll be using this when the talk of Generosity come up again in the later parts.)

By finding the extremes of the virtues he wishes to find this mean as a reminder of logical conclusion in pursuing a virtuous life.

2) Practice does make perfect.

The proposition being made in this statement is the fact that Aristotle says that in order to cultivate virtue it must be practiced in repetition. In other words, virtue is a habit rather than just conscious choice. Though of course, Aristotle makes it noted that virtuous habit is a good choice, it's the conscious repetition of good choices that promote moral flourishing.

The virtue is habit principle is a common motif when Aristotle talks about when people make good choices to better their lives in the long run but he also talks about the consequences of making habits of bad choices. Lack of virtue can be improved on and can still be promoted when some people are good in some virtues and lack in others. Since virtue is habitual, it can be taught and practiced. And continued practice leads to a better life.

3) The Importance of Friendship

Aristotle noted that there are 3 kinds of friendship we all face. But let me explain what he constitutes as a friendship. This is crucial.

Aristotle notes that a "friendship" of one good person and one bad person can't be considered one due to the nature of the bad person and his motivations for being friends with him (the good person). It's an obscure example but let's look at Peter Keating and Howard Roark from The Fountainhead. Peter can only befriend people for his self-esteem and pride. He has none as an architect because he was put in that position by his mother and his friendship with Roark is only a means to help him ensure himself as a good person. He may not be as bad as other characters like Darth Vader, Hannibal Lecter, or Shou Tucker,(URGHHH! I HATE THIS BASTARD SO MUCH! Anyone who isn't a fan of anime or has never seen Full-Metal Alchemist might want to watch the show to see why we anime fans get worked up about dogs and wigs.) but his weakness in virtues does make him a bad (though somewhat pitiable) guy,

Even if both parties are bad in the relationship, they could never work out a means to goodness and virtuosity in friendship. Look at Hitler and Stalin for a good example. Both are notorious dictators and yet formed a friendly alliance where. in the end, one (Hitler) betrayed the other (Stalin).

And now, let's look at the 3 main examples of friendships,

I) Friends for Pleasure: These friends are the types of friends you come together with to enjoy your lives with. Like going to the movies, amusement parks, having drinks, etc. When good and compatible friends go out, their entertainment is doubled due to good company.

II) Friends en stratagem: I have personally coined this phrase but I can't say confidently that it's original for these kinds of relationships have happened in the past so many times. These are similar to business and political ends primarily, though not always in association with it. It's a strategic friendship to make allies in a certain circle and usually ends with a "you scratch my back and I'll scratch yours" issue. However, the two in this situation must be friends and have been in good standing and virtue to achieve a healthy relationship. (Evil on one or both sides can't apply.)

III) True friends: These are the friends Aristotle Praised the most. They share your feelings with you, can be able to open up about things you might be too sensitive to talk with others on, and such. They are just like you yet not so. Two good people who see the benefit of each others company, not just for Pleasure or gain, can find the end in itself in this situation.

4) 11 Virtues are Necessary for a Flourishing Life

There are 11 Virtues Aristotle mentions in his book. All are varied in length of discussion but he does mention they are between two radical extremes.

I. Courage: The be brave when the moment is needed. In excess, it's recklessness that does lead to abandoning and in regress, it's cowardice which enables fear and lack of standing to anyone when needed.

II. Generosity: To be charitable, to the right people, at the right time, and in the right mindset. Excess is profligacy (giving out too much money rashly and showboating it) with the regress being Stinginess or Miserliness (withholding all money and goods.)

III. Temperance: The rational control in pursuing earthly desires. Debauchery is the excess of the loss of self-control. Scarcity is the regress of temperance in refusing all earthly desires. (A monks life one could say.) Noting this, Aristotle promotes being able to enjoy yourself within the means rather than this ascetic lifestyle.

IV. Magnanimity: Generally, translations of this have included greatness of soul but I'll also use pride to explain this. This virtue is the feeling of accomplishment and the right way to showcase and promote it. The excess discovered is Vanity (pride with no real accomplishment or such) and the regress is described as the smallness of soul. (To be honest, this could be due to literal translations of the Ethics. Some use Pusillanimous (Latin for the small soul so it does fit in a way))

V. Magnificence: How to carry one's self. A form of pride in how one is presented with their affluence and wealth. Vulgarity is the excess and the regrees is Pettiness.

VI. Indignation: A form of envy where people attack the misrepresentation of justice in society. (Aristotle uses the words Righteous Indignation to further emphasize the mean as well as how people can carry indignation into the excess and regresses of Envy (which Aristotle believed was an evil in itself but that's another story.) and Spitefulness(sometimes called Malicious enjoyment, and some like to also call it Schadenfreude (Thank you Avenue Q)).

VII. Patience: To be calm and focused in situations and with other people. The excess of Patience is Irrascability (impatientness) and the regress is described as Lack of spirit. (It's hard for me to say what this is but I guess it could be also described unambitious though I don't think this is the right word either.)

VIII. Truthfulness: The truthfulness Aristotle is dealing with is Truth of oneself and one's accomplishments. Beware of Boasting (the excess of promoting one's self in exaggeration) and of self-depreciation (the regress which can also be called understatement).

IX. Wittiness: The virtue of being clever with words as well being serious and joking at the right times. The excess is buffoonery (the man who takes everything as a joke and nothing serious) and the regress being boorishness (the man who takes everything too seriously and can't stand a joke).

X. Friendliness: The ability to get along with the right people. The excess being a flatter with no substance whatsoever to critique and the regress being curmudgeonly when one is unfriendly and constantly avoids others and society.

XI. Modesty: The virtue to accept and understand shame. (Aristotle didn't necessarily make this a virtue but that it was a good character trait to have. I would argue it makes a good virtue if understood.) The shameless are in excess due to never feeling shame and the shy (not the same way as we see shy people but how they react to their actions) as regress due to feeling shame for all actions even when (most of the time) their actions have nothing to be ashamed of.

5) "Reason" is absolute to a good life

Ayn Rand said she had an enormous debt to the Philosopher Aristotle for his foundation of Metaphysics and Epistemology had led her to formulate the Objectivist Philosophy. And why shouldn't it?

"Reason" is the primary driving force in making good decisions in life and thus Aristotle talks back to reason as it is "reason" that makes good choices and instinct that, often much more than not, leads us to bad choices due to not reasoning out and thus making an effort into understanding our choices before us.

Thes 5 points are crucial in understanding one of the most important ethicists in our entire human existence and I hope I got some of you interested in reading his Ethics, though a bit of a warning, it is a heavy read so also prepare for a little light reading. (Just like the next book I'll be reviewing: The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty by Anne Rice.)

Stay Tuned Darlings!

No comments:

Post a Comment